Welcome to FT Asset Management, our weekly newsletter on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar global industry. This article is an on-site version of the newsletter. Sign up here to get it sent straight to your inbox every Monday.

Does the format, content and tone work for you? Let me know: harriet.agnew@ft.com

One thing to start: we’re taking an Easter break next Monday. Normal service will resume on Monday April 8.

‘What sense is being a billionaire if you’re not a bully?’

Palm Beach is having a bit of a moment right now and no one is more aware of it than Nelson Peltz, for whom it’s been his stamping ground since the 80s. I went to the island to do a Lunch with the FT interview with the octogenarian activist investor, founder of Trian Partners, and of course father-in-law of Brooklyn Beckham, in his natural habitat.

“This place has become unlike any place in America,” he told me. Referring to the cut-and-thrust culture and low-tax regime that have lured magnates to southern Florida, he added: “You’ve got so many meat eaters, carnivores . . . All my friends live on the same street” — South Ocean Boulevard, a stretch of ultra-exclusive waterfront properties bordered to the east by the Atlantic.

Peltz, 81, is best known for his turnaround campaigns at big consumer goods companies such as Mondelez, Heinz and Procter & Gamble. Right now he’s waging his second proxy fight in as many years at US entertainment group Walt Disney; he’s trying to sharpen up Unilever, the maker of Marmite, Dove soap and Hellmann’s mayonnaise; and he’s “reluctantly getting involved in US politics again”.

Peltz has a deep voice, a piratical charm and an uncompromising approach — “a case of the cure being worse than the disease”, says one critic. The wedding planners he hired six weeks before his daughter Nicola’s wedding to Beckham Jr and let go nine days later dubbed him a “bully billionaire” in a lawsuit.

“A what billionaire?” he shoots back when I ask about this.

“A bully billionaire.”

“That’s probably true,” laughs the man sometimes known as the smiling crocodile. “What sense is being a billionaire if you’re not a bully? Let me tell you something . . . They got a great deal for doing nothing. But that’s water under the bridge.”

Read the full interview here, in which we talk about “woke” superheroes, keeping politics out of business — and why he’s backing Donald Trump again. Oh and that topless tennis story. Meanwhile don’t miss this recent Vanity Fair feature on why Palm Beach is having a “category 5 identity crisis” . . .

The mutual fund at 100: is it becoming obsolete?

One hundred years ago last Thursday, Edward Leffler, a former door-to-door salesman of pots and pans, revolutionised financial markets. His invention, the open-ended mutual fund, allowed retail customers to buy into a diversified portfolio of stocks and be confident that they would get a fair value when they wanted their money back.

Leffler’s innovation gave lower and middle class people an ownership stake in American capitalism. It also spawned financial titans like Fidelity and Vanguard and thousands of smaller competitors that together employ hundreds of thousands of people.

Mutual funds manage nearly $20tn in US assets and about $63tn worldwide, including everything from stakes in fledgling tech start-ups to government bonds. More than half of all American households and 116mn of the country’s 333mn residents hold shares in at least one mutual fund.

“The mutual fund has democratised investment. It has made investing accessible to the average person in an incredibly durable way,” says Jody Jonsson, vice-chair of Capital Group, the world’s largest active fund manager.

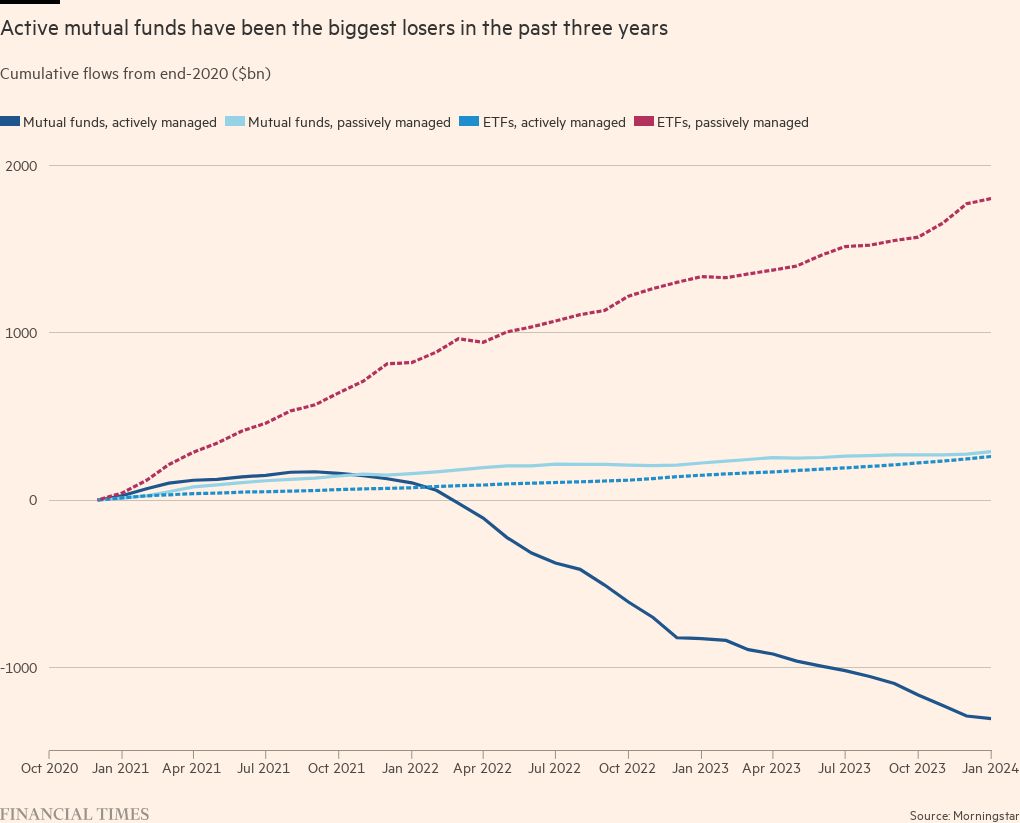

But, as Brooke Masters, Will Schmitt, Madison Darbyshire and I explore in this Big Read, today the mutual fund’s dominance is under threat from newer rivals that promise tax advantages, lower fees and rapid trading. US mutual funds suffered more than $1tn in net outflows from January 2021 to December 2023. While they gathered about $13bn in net inflows in February, it was the first time they had a positive month in two years, according to Morningstar, a data group.

The active stockpicking funds that have been the industry’s bread and butter have suffered the biggest decline as a newer option, exchange traded funds, amassed more than $2tn in inflows in the US since January 2021, including more than $575bn last year alone.

Some industry observers predict that the glory days are ending. US money managers showed the world how to help ordinary people share in modern public markets. But as the mutual fund celebrates its 100th birthday, many investors want something faster, cheaper or just different. Unless asset managers adapt, many of them — and one of the most successful financial products of all time — could slowly slide into irrelevance.

“It’s inexorable,” says John Rekenthaler, who has been tracking mutual funds for Morningstar since the 1980s. “I don’t see what a mutual fund can do better than [an] ETF . . . It’s a better mousetrap . . . Eventually the mutual fund is dead.”

Read the full story here

Chart of the week

UK stocks are trading close to a record discount relative to their Wall Street counterparts, luring some bargain-hunting investors back to the country’s battered stock market, write Stephanie Stacey and Costas Mourselas in London.

London-listed equities have lagged behind peers in recent years as heavyweight sectors like banking and energy have failed to keep pace with the rapid growth of technology stocks, and political uncertainty following the 2016 vote to leave the EU weighed on the market.

While US and European indices have chalked up a succession of record highs this year, the FTSE 100 has yet to eclipse its February 2023 peak, despite enjoying its best week since September as investors have become more confident that the Bank of England will deliver multiple interest rate cuts this year.

UK stocks have long traded at lower valuations than US markets, but recent underperformance has left the UK market looking particularly cheap. Forward price-to-earnings ratios — a commonly used valuation metric — of stocks on the MSCI UK index are 47 per cent lower than those on the US equivalent, according to asset manager Schroders. The 48 per cent discount in January was the largest in data going back to 1988.

The transatlantic gulf reflects a lack of investor enthusiasm for the UK market, which is heavily weighted towards sectors like banks and mining, and lacks the high growth technology stocks that have powered Wall Street’s rise. Some UK companies have pointed to higher valuations when choosing to list in New York rather than London.

Bank of America’s latest monthly survey, published on Tuesday, found that fund managers remain net 27 per cent underweight in the UK, and have been consistently underweight since July 2021.

Still, cheap UK stocks are starting to grab the attention of fund managers.

“The thing that gets me excited about UK equities is just the amazing value that’s on offer within the market”, said Alex Wright, a portfolio manager at Fidelity International. He prefers value stocks, which could benefit as we “return to a more normal inflation and interest rate environment”, and said financials are the largest position in his portfolios.

Five unmissable stories this week

Activist investor Elliott has built a 5 per cent position in Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust, whose early bets on tech groups such as Amazon turned it into one of the UK’s most popular investment vehicles before falling out of favour over the past two years. The emergence of Elliott as an investor comes a week after Scottish Mortgage announced a £1bn share buyback in a bid to support its own stock.

Nearly two years into a Republican campaign to punish BlackRock for insisting that climate change carries financial risk, red state investment funds have pulled about $13.3bn from the world’s largest asset manager. That figure is roughly one-tenth of 1 per cent of BlackRock $10tn in assets under management, and some Republican state pension funds still have well north of $20bn parked with the money manager.

Inside the daring raid on Barings that has shaken the $1.7tn private credit market. More than 20 senior executives have defected to a brand new business set up by an Australian real estate veteran: Paul Weightman’s Corinthia Global Management. The audacious move has ignited a rare public feud in the asset management industry: on Monday Barings filed a lawsuit against two of its defecting executives and Corinthia.

Andrea Rossi, the chief executive of investment group M&G, has said he wants to take advantage of under-developed private credit markets in Europe and expand the business in private assets, amid warnings of the impact of higher interest rates on the asset class. In its full-year results, M&G reported a 28 per cent rise in pre-tax adjusted operating profit in 2023, to £797mn, beating analysts’ expectations.

Calpers, the US’s biggest public pension plan, is to increase its holdings in private markets by more than $30bn and reduce its allocation to stock markets and bonds in an effort to improve returns. The formal approval comes two years after it admitted that a decision to put its private equity programme on hold for 10 years had cost it up to $18bn in returns.

And finally

Portraits to Dream In — the blazing talents of Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman. The National Portrait Gallery’s dreamy pairing of the photographers obscures what really connects their work across the 19th and 20th centuries, writes our chief art critic Jackie Wullschläger.

Thanks for reading. If you have friends or colleagues who might enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to them. Sign up here

We would love to hear your feedback and comments about this newsletter. Email me at harriet.agnew@ft.com

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

Working It — Everything you need to get ahead at work, in your inbox every Wednesday. Sign up here